Zen and the Art of Harry Dean Stanton

His swan song, "Lucky," comes to VOD

The great, gaunt actor Harry Dean Stanton (“Alien,” “Paris, Texas,” “Repo Man,” a zillion others) left us at the age of 91 in September of 2017. Less than a month later, like an unexpected bequest, “Lucky” was released to theaters – a fond final starring role for a performer who too often made his mark from the sidelines. It’s a shaggy dog of a movie but a lovely and profound one, and why it took four years to come to video on demand is anyone’s guess. Stanton himself might say that things just take their time, in their time. Anyway, it’s here, streaming on HBO Max and available for rent almost everywhere else. Attention must be paid.

Stanton actually shot one more movie a month after “Lucky” completed filming in July 2016 – a supporting role in the poorly received “Frank and Ava” – but his penultimate film was built around the actor the way you might build a church around a tree. Stanton’s the Lucky of the title, an old coot in a dusty desert town where everyone knows everyone and everyone gets along; the film was shot in Piru, California, about an hour north of L.A., with some Arizona sequences featuring saguaro cacti that are even older than Stanton. Familiar faces line the streets and the barstools: Barry Shabaka Henley as diner owner Joe; Ed Begley, Jr., as a town doctor astounded that Lucky’s still standing; David Lynch, who cast Stanton in four of his movies and one TV show, as an old friend mourning the disappearance of his pet tortoise, President Roosevelt. Yvonne Huff Lee, who’s new to me, plays a diner waitress who drops by to check up on Lucky and ends up getting high with him while watching Liberace videos.

That makes “Lucky” sound like a goof, a quirkfest, and it’s anything but – the movie’s immensely pleasurable while at the same concerned with matters of the utmost importance. The only matters that matter, really. Lucky has made it this far by taking each day on its own; he doesn’t believe in God and he doesn’t believe in an afterlife. Every morning he comes into the diner to do his crossword puzzle and greets Joe by saying “You’re nothing,” to which Joe cheerfully responds, “You’re nothing.” But one morning early in the film, Lucky has a fainting spell while making his coffee, and suddenly Nothing seems awfully close at hand. The conflict in “Lucky” is between an old man and the Void, and there’s no doubt at all about who’s going to come out ahead.

So “Lucky” is, in its fluky way, about regret and memory and grace – the big stuff. And fear – an honest fear of the end. That fear rattles Lucky, makes him act pissy toward old friends and downright nasty to an insurance salesman (Ron Livingston) who represents a cashing in on death that the old man finds appalling until the salesman tells of his own brush with mortality. The movie’s as casual as an old sock, but every moment in it is freighted with an awareness of life’s fragility, the luck we have to be here, and the difficulty in accepting the notion that someday we won’t.

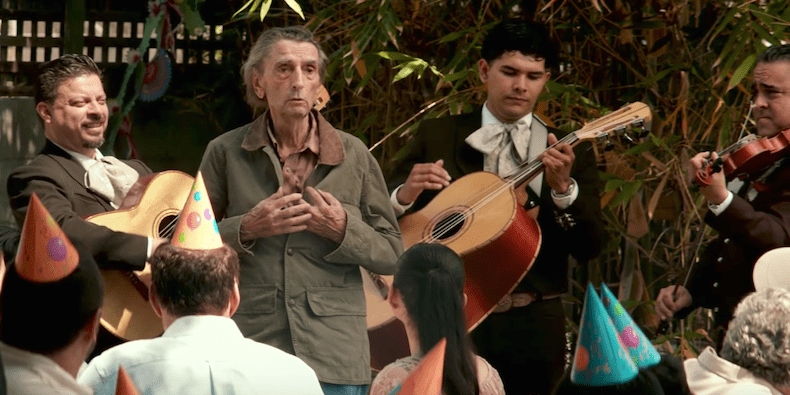

The director is John Carroll Lynch, himself a character actor of no small skill, and the script was co-written by Logan Sparks, Stanton’s longtime assistant. The movie makes an excellent companion piece to the 2012 documentary “Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction,” which can also be rented online and which features many clips from the actor’s career – I’d forgotten Stanton was in “Cool Hand Luke,” playing guitar and singing “Just a Closer Walk with Thee” in a fine, high mountain voice. He sings in “Lucky,” too – a quavery but tremendously moving rendition of the Mexican ranchera song “Volver, Volver” that brings a backyard birthday party to a hushed standstill.

The whole movie’s like that: Full of moments that are completely present while rippling out to the past and beyond the movie’s frame. A diner counter conversation between Lucky and an ex-Marine — both veterans of World War II – is spectral with recollections of carnage and loss while incorporating details of Stanton’s own Navy service; the actor opposite him is Tom Skerritt, who served with Stanton on the good ship Nostromo in “Alien.” A shot early in the film – one of my favorite images in recent movies – has Lucky walking past an old saloon now gutted and serving as a parking garage, and right there is the history of the American West and the Hollywood western.

Stanton himself was a non-believer, but he was on record as leaning toward the Buddhist/Taoist side of things, and “Lucky” makes a case for the actor as one of the few legitimate Zen saints of the movies, along with Bill Murray, Larry Fine, and Greta Garbo. (All other candidates will be considered.) He talked a lot about nothingness in interviews, like the closet hippie he was, not as a form of nihilism but of reassurance – a way of marveling that each of us is just a mess of electrons whirling around with gulfs of space between them. Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.

Harry Dean Stanton is no longer here in body and he didn’t believe in the soul. All that’s left of him are his movies. All that’s left of him is light.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

Or subscribe. Thank you!