What Was Your First Album?

On the vanished joys of music ownership. Plus: "Rothaniel" on HBO Max and J.M.W. Turner on the walls and onscreen.

What was the first album you bought? That you bought, rather than someone picking it for you. What was the moment that you began setting the parameters of your musical taste for yourself?

I ask because as I was making dinner last night I threw on a Byrds playlist and when “Eight Miles High” came on, I was whisked back in time to 1966 and a small, long-vanished record store among the gallery shops of Boston’s Prudential Tower. I was nine and with my mother; maybe we’d come down from a visit to the Top of the Pru skywalk, then two years old and still a novelty. She bought an LP my older sister had been requesting – no idea which one but I’ll hazard a guess and say Simon and Garfunkel’s “Sounds of Silence” – and then, out of the blue, asked me to choose an album for myself. A pivotal moment! The chance to have an opinion, appear informed, be seen as possessing an aesthetic! To be seen, period, which when you’re the youngest in the family counts for a lot.

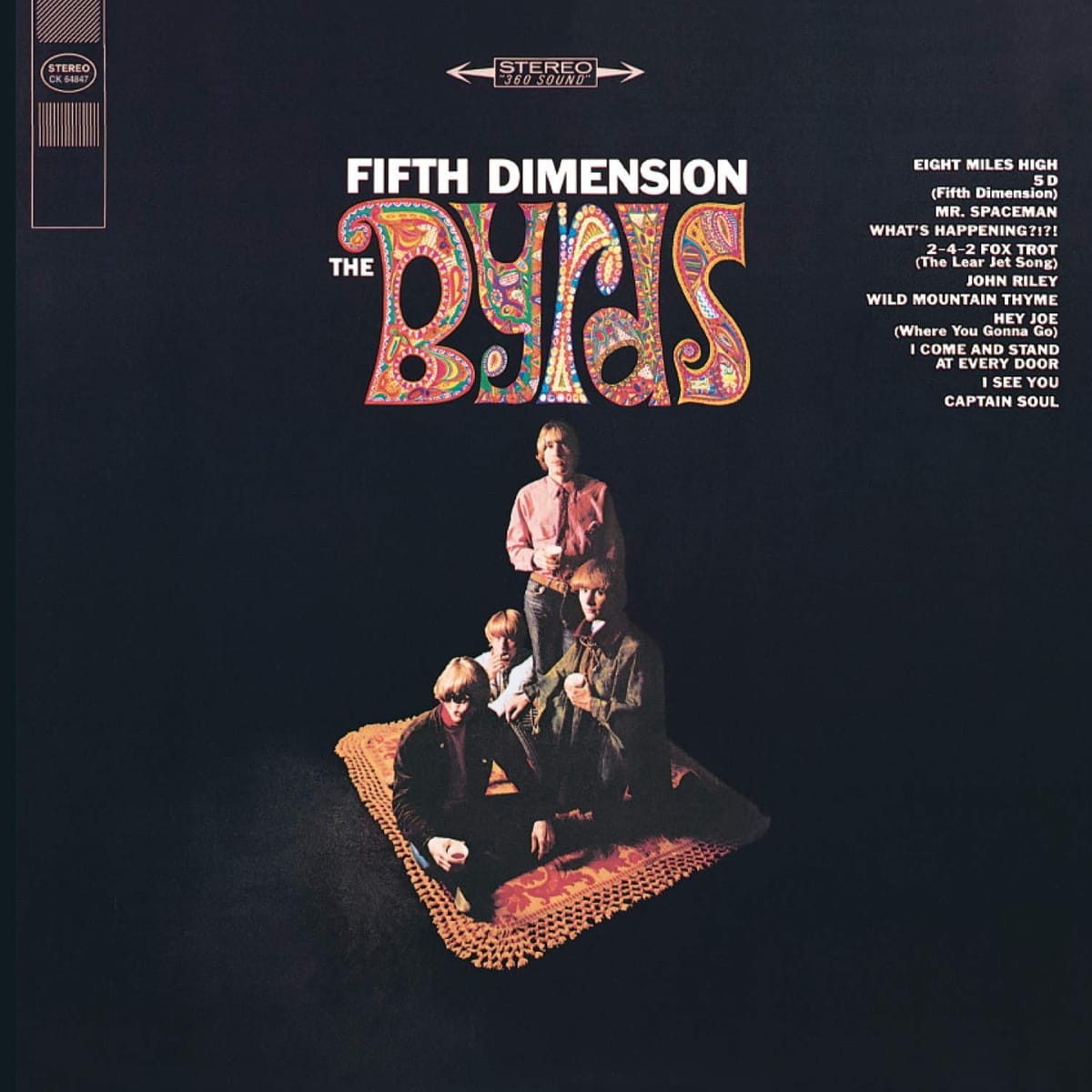

I remember pondering the matter and opting for “Fifth Dimension.” Had I heard “Eight Miles High,” the breakout single, on the radio? Probably. Did I know who the Byrds were? Possibly. I doubtless thought the cover was cool because it still is, the group clustered on a carpet that appears to be floating in a vast, inky void, the band’s name psychedelically spelled out above them. It wasn’t the first record album I bought on my own, with my own money – that came later. But it was mine, and as a kid brother in a family where older sisters set the musical agenda, it was important that I perceived “Fifth Dimension” as a record only I would have chosen. I listened to it with a proprietary obsessiveness for weeks, entranced by the single’s acid-freakout guitars (modeled after Coltrane), the gorgeous, piled-up harmonies of “Wild Mountain Thyme” and “John Riley,” the aliens-ate-my-weed comedy of “Mr. Spaceman.” Listening to the album again last night, I realized I still felt a sense of ownership – a flag I planted, or it planted in me.

A few months later, I bought my first 45 r.p.m. single, the preferred format in a hit-driven era. It was “Happy Together” by the Turtles, and I was cheered by the song’s bouncy optimism, not realizing that the entire thing was a fantasy in the head of a man too shy to talk to his dream girl. Somewhere along the line I picked up or was given “The Mason Williams Phonograph Record,” a relic of its time with Swingle Singers-style vocal arrangements, studio strings, a lot of sub-Nillsson feyness, and a big fat jive-flamenco hit in “Classical Gas,” which I thought was the coolest thing I’d ever heard for about a month and a half.

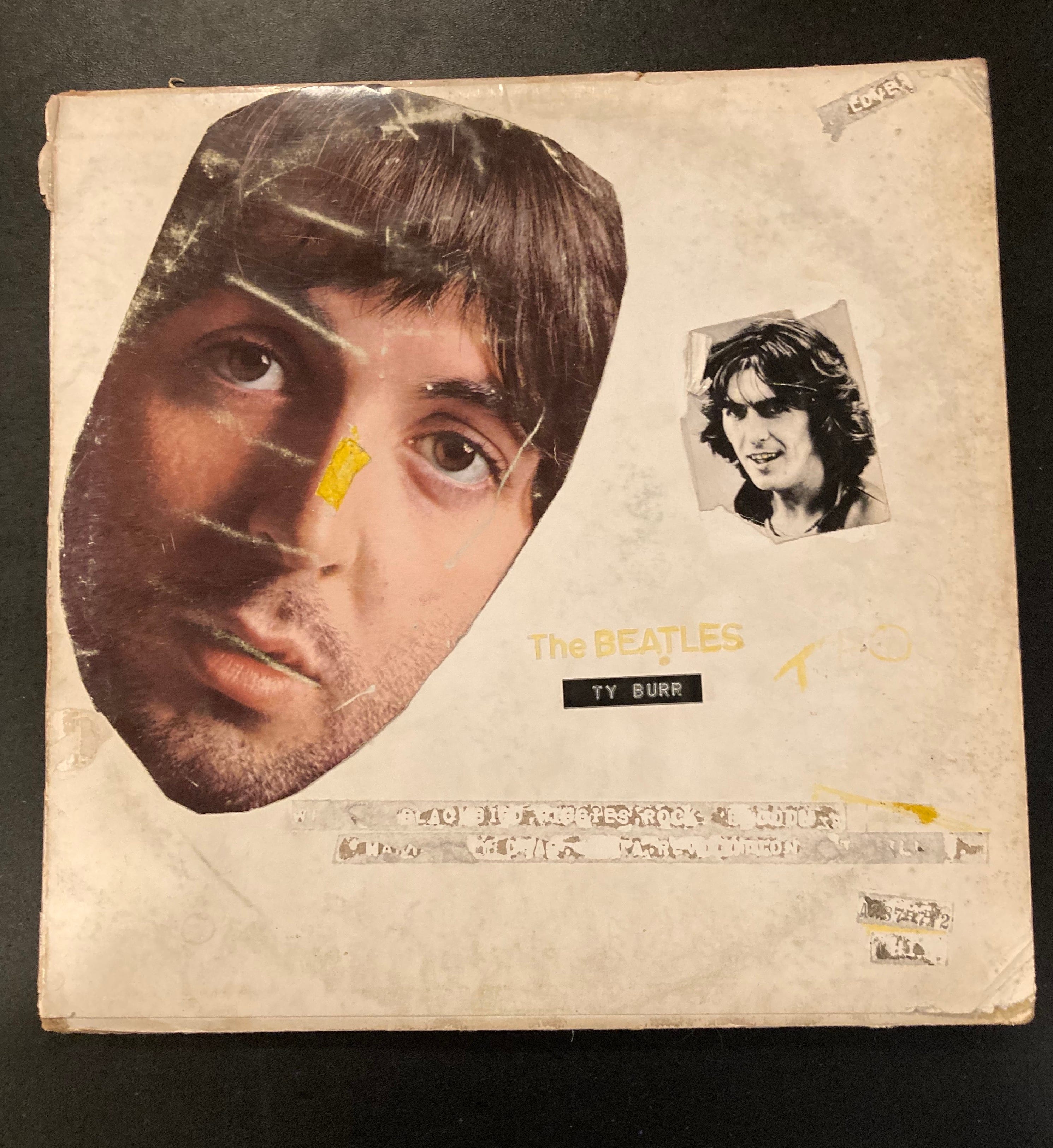

But the first album I bought – saved up my allowance, went out, and purchased on my own – was “The Beatles,” aka The White Album, in late 1968, and the significance of that within the family narrative was immense. My older sister was almost 13 when the Beatles hit America like a ton of bricks in early 1964 – she was smack in the center of the demographic. She saw them in concert (chaperoned by my dad, who didn’t even like jazz and who thought the Fabs heralded the end of civilization), and she had the first seven U.S. album releases, starting with “Meet the Beatles” and running through “Rubber Soul.” Six years younger than she, I saw her as ineffably worldly. She listened to Françoise Hardy records – how much more sophisticated could you get?

My middle sister concentrated on singles – carried to sleepovers in a plastic case with embossed daisies on it – but picked up the Beatles baton with the next release “Revolver” (still my personal favorite of their albums) and carried through to “Sgt. Pepper” and “Magical Mystery Tour,” after which, through some unspoken genetic calculus, it became my turn. Nothing was said. I just wanted the next one and must have gotten it first: A double album, mysteriously minimalist and gleaming, all the artwork crammed inside on a poster along with four 8x10 glossies of John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Seeing the cover as a blank canvas, I cut up the photos and the poster and glued the pieces to the front and back of the gatefold, destroying the album’s value as a collectible but stamping it as wholly and indisputably mine. (Literally stamped, since I adorned it with embossed song titles made with one of those old ka-chunga Dymo label punchers.)

It's still mine.

It’s become clear that “owning” a piece of music – of treating its physical possession as both intensely personal in meaning and an advertisement for oneself – is an experience that had only a brief moment in the history of culture. After the invention of recorded sound and before the rise of streaming; a century or so. Prior to the wax cylinder, you could hear music played live (or play it yourself) and you could buy the score on paper, but you couldn’t purchase or appropriate the sound and replay it to your heart’s content. Today you can select from an ocean of recorded content that only seems infinite but you never hold it in your hands and you never stop paying for it. Do my own kids think of songs and albums they love as “theirs”? Or just their generation’s? There’s a need, still, obviously, or there wouldn’t be a retro vinyl boom. From cylinders to 78s and LPs to CDs, we got used to the tactile pleasure of something we could previously only hear. What will happen in another generation, when music will once again just be something in the air? And why have I held on to all my albums and boxed sets, 45 singles and C-90 cassettes, when I listen to everything on Spotify? Am I afraid that if I let them go, my past will disappear – or that I will?

If you watched Saturday Night Live last weekend, you might have been brought up short by its host, a genially soulful stand-up comedian named Jerrod Carmichael who wasn’t widely known before but who’s now having a moment. He has a new special on HBO Max, “Rothaniel,” that’s alternately hilarious and profound and sometimes both at the same time. Sitting in a darkened club, Carmichael muses on family secrets and the ways they bind and warp: His father’s other family, for one thing, or the queerness the comic himself kept under wraps until recently. It’s especially striking to see a Black stand-up address his gayness in front of an at least partially Black audience, and as “Rothaniel” moves into deeper and more raw waters in its final third, the questions and expressions of support that softly float up from the audience — unscripted — are incredibly moving. Comparisons are being made to Hannah Gadsby’s two groundbreaking specials, but Carmichael is more ruminative and wry. He sees the humor in the worst parts of life and the tragedy in the jokes. The director-editor is Bo Burnham, whose own 2021 special, “Bo Burnham: Inside,” was one of the greatest things last year gave us, and the two men use silence here daringly, as a kind of pained pause button and an aural correlative to Carmichael’s wracked body language. It’s a remarkable hour of human comedy that lingers long into the night; I couldn’t recommend it more highly.

If you’re in the greater Boston area (as many of my readers are), you should do yourself a solid and go see the career survey of J.M.W. Turner paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts. On display until July 10, it’s titled “Turner’s Modern World,” a label that references both subject matter and style. The exhibition is centered around Turner’s 1840 “Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On),” a terrifying documentation of a history many wanted to deny back then and still do today. Just as startling is the painter’s technique, which prefigured Impressionism by a good 60 years and, in the later work, leapfrogged ahead into something very near to Abstract Expressionism, an approach that discombobulated the majority of his audience in early-Victorian England — the Queen herself called “Sunrise with Sea Monsters” (1845) a “dirty yellow mess” — while enrapturing a growing minority in his time and in the years to come.

Today, Turner’s a rock star among dead painters; if not up there with Monet and Rembrandt and Picasso, then getting close. He is one of the few painters with the ability to regularly take one’s breath away; standing before a work like “Snow Storm — Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth” (1842) or “Norham Castle, Sunrise” (1845) or “Venice with the Salute” (1845), it’s as if reality itself has been atomized into elements of water, air, and light. We are very small in Turner’s world.

What are the great movies about painters? “Lust for Life” (1956) and “Vincent and Theo” (1990) about Van Gogh; Peter Watkins’ “Edvard Munch” (1974), “Frida” (2002), “Andrei Rublev” (1966). “Camille Claudel” (1988) if you want to include sculptors. Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1956 “The Mystery of Picasso” always blows my mind because you get to see the artist himself birthing his creations on the spot. “Mr. Turner,” the 2014 film by Mike Leigh certainly belongs in this company. To quote from my 2015 Boston Globe review:

Leigh is an acknowledged Turner fanatic, and his achievement here — with the invaluable contributions of cinematographer Dick Pope and production designer Suzie Davies, among others — is to visually replicate the shades and atmospherics of Turner’s art and situate them in his filmed world. So many scenes in “Mr. Turner” open in long shot, a busy human landscape below dwarfed by the high drama of sunlight and clouds above, colors far beyond the scope of an artist’s palette, and way down in a corner, the solitary figure of Mr. Turner (Timothy Spall) trying to put it all on canvas.

There’s not much plot to the film, which caused some grumbling on the movie’s release, but as I said back then:

A life is not plot; plot is not life. By scrupulously sticking not just to the accuracies of Turner’s life as we know them but to the tiniest of details, the chipped mugs on kitchen tables, the pantaloons on a passing merchant, the spray of storm surf across the bow of a ship, Leigh wants us to truly see the world Turner moved through. Only by seeing that world can we see how he saw and painted it. “Mr. Turner” is an attempt to reverse-engineer a pathway into an artist’s mind.

See the MFA show and watch the movie. Or see the movie, then go to the MFA show — either way, you stand to be transfigured.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.