What to Watch: "Poor Things" and "The Boy and the Heron"

A double shot of four-star fantasy from Japan's master animator and Greece's bad-boy auteur.

Two of the most visionary movies of the year open today, and when I say “visionary,” please understand that I’m understating the matter. There are films one values for their naturalism, the care with which they replicate the pace and feel and room tone of lived life. “Past Lives” and “The Holdovers” are excellent 2023 examples of the form. Other movies invent realities that serve as funhouse reflections of our joys and concerns, and when the invention is so thorough, so fearless in its service to artistic will rather than the demands of the marketplace, the results can be both terrifying and liberating. So when I tell you that Hayao Miyazaki’s “The Boy and the Heron” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐, in theaters everywhere) and Yorgos Lanthimos’ “Poor Things” (⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐, opening in NY and LA, rolling out to other cities Dec. 15) can raise a moviegoer’s pulse rate to a pitch of discombobulated elation, I hope your first instinct is to simply go. Instinct – their makers’ creative imagination at firehose force – is where these two voyages of discovery arise from, and an instinctual response is what they demand in return.

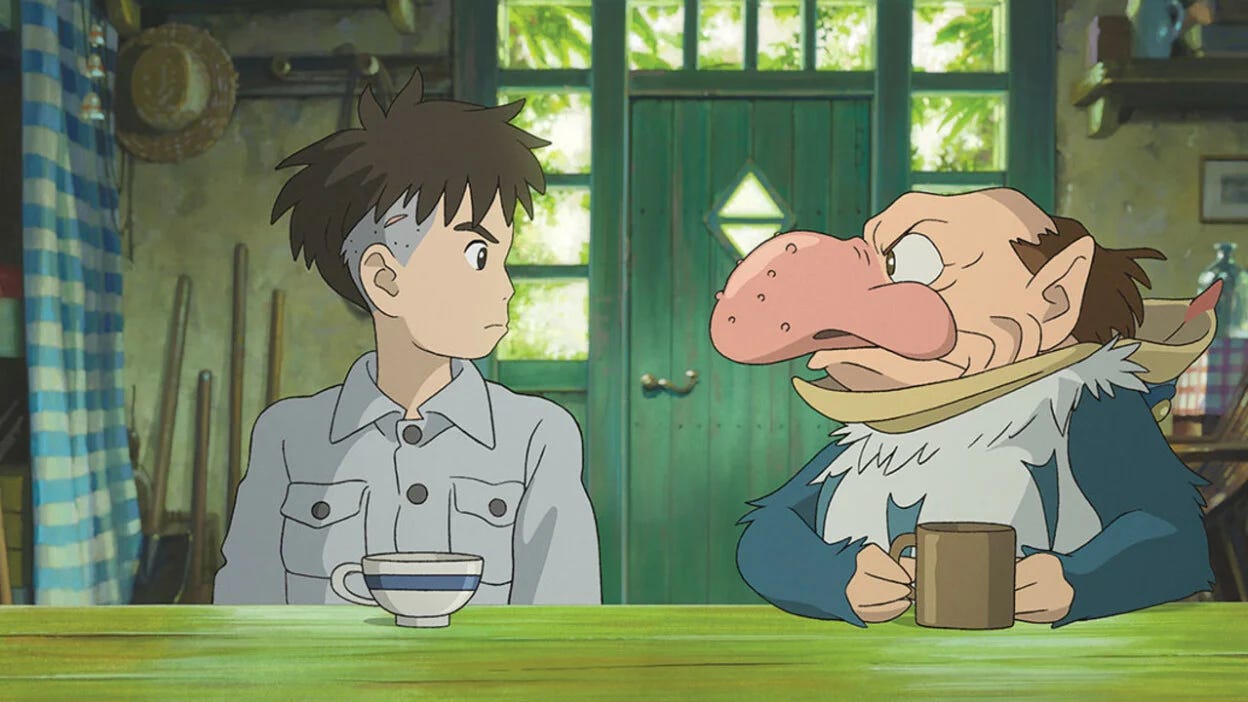

“The Boy and the Heron” is supposedly the final work from the 82-year-old Miyazaki, but he has said that before; Japan’s master animator has retired more times than Cher. The new film has a sense of summing up, though – of emotional confrontation if not closure – that earlier Studio Ghibli masterpieces like “Princess Mononoke” (1997), “Spirited Away” (2001), and “Howl’s Moving Castle” (2004) have lacked. “The Boy and the Heron” stands with those peaks in its heady, sometimes baffling mix of visual and thematic elements: “Alice in Wonderland,” Japanese folklore, Jungian archetypes, the disorienting perspectives of manga, and a strain of personal loss viewed through a scrim of hectic surrealism that can only be called Miyazakian.

The boy of the title is named Mahito, and he has lost his mother in the WWII firebombing of Tokyo, whose depiction at the start of “The Boy and the Heron” is an apocalyptic reminder of Studio Ghibli’s bleak anti-war classic “Grave of the Fireflies” (1988). Relocated to the country, where his war industrialist father has moved his operations, Mahito is lured by a raspy-voiced grey heron into a series of psycho-fantasy netherworlds. That’s as close to a plot synopsis as it’s worth bothering with, and, like most of Miyazaki’s ambitious later works, “The Boy and the Heron” is often richer in emotional and visual sensation than straightforward narrative. It’s not really a kids’ movie, and while there’s nothing here that seems to have erupted from the subconscious beneath a child’s bed – like No-Face in “Spirited Away,” who unnerved one of my young daughters so thoroughly that we had to remove the DVD from the house – Miyazaki is grappling with a child’s confusion, anger, and loss through the filter of adult memory. This is a movie for older kids, their parents and grandparents, and for young adults – anyone still turning over the wreckage of the statues from their childhood.

But, okay, yes, there is that army of giant parakeets wielding carving knives – they seem to have wandered over from a “Far Side” cartoon – and a bustling gang of grannies that suggest a Hadassah chapter of the Seven Dwarves, and adorable blobby creatures called warawara that float away like an airborne army of bubble tea pearls. The heron turns out – spoiler alert – to be inhabited by a snarky little demon who bears a passing resemblance to one of R. Crumb’s Snoids; the character’s another archetype, the untrustworthy comic sidekick. At Miyazaki’s simplest and most animist – say, the eternal “My Neighbor Totoro,” from 1988 – he can evoke the comforting immensity of our dream worlds. In “The Boy and the Heron,” the hero is older, and the dream keeps pirouetting to the edge of nightmare. The film was originally called “How Do You Live?,” a title it shares with a 1937 literary classic by Genzaburō Yoshino – a sort of Young Adult novel of ideas – that almost every Japanese schoolkid has read and that Mahito’s mother leaves him a copy of. Yoshino’s book ends with the author asking the reader “How will you live?” and this wild, uncategorizable film asks the same question of its hero and its viewers, this time from the point of view of an aging artist looking backwards through the telescope. How have I lived? Miyazaki could be asking himself, and “The Boy and the Heron” conjures up a parable of magic and mastery that never quite solves the enigma of being. I suppose he’ll just have to make another movie.

“Poor Things” is – are you ready? – even crazier. It’s another pilgrim’s progress, a coming-of-age story more linear than Miyazaki’s but saltier and smarter, and outrageously confident in its outrageousness. Lanthimos’s films are strong stuff: I admired “The Lobster” (2015) without much liking it, and I hated “The Killing of a Sacred Deer” (2017) while being coldly impressed. But then came “The Favourite” (2018), which was a dark satire of royal bad manners and bed-hopping, Queen Anne division, and it introduced the world to a friskier, riskier Emma Stone while serving notice that the Greek director’s ambition had gone up a notch.

“Poor Things” takes it up another ten. Stone is back, this time at the dead center of the story as – well, as what, exactly? Adapting Alasdair Gray’s 1992 novel, Lanthimos and his “Favourite” co-writer Tony McNamara have fashioned a mad reworking of “Frankenstein” in which the monster is a woman, Bella Baxter (Stone). Bella is the creation of Dr. Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe, below, sporting a face that looks like it’s been stitched together at a drunken quilting bee), but Bella just calls him God. When she gets around to developing language, that is; without giving too much away, I can reveal that the poor thing has the mind of a newborn, and the path Bella travels through the movie is that of a baby toward maturity, all the while in a grown woman’s body.

Stone’s performance is on one level an almost freakish display of physical technique. Bella walks like a toddler in the early scenes, top heavy and stiff-legged, and her impulse control is underdeveloped, to put it mildly. Very young children are all Id and little Superego, but seeing that in an adult is a sight the film’s 19th century characters are hardly prepared for, much less in a woman. Least of all when Bella discovers sex, or, as she calls it, “furious jumping.” The film’s bedroom scenes are enthusiastic and frank, a reminder that American filmmakers are far more comfortable showing pain than pleasure. Lanthimos, good European that he is, swings both ways.

“Poor Things” is a picaresque in which a woman made by a man becomes a self-made woman, by trial and error, instinct and intelligence, love and anger and pity. The film’s men are a comically ripe shooting gallery of types: The damaged doctor-father; his meek assistant (Ramy Youssef), prostrate with love for Bella; a sleazy roué of an attorney, wonderfully played by Mark Ruffalo as a masher out of a Victorian stage melodrama. Lanthimos has a magpie’s eye for casting: When Bella embarks on an ocean crossing, her shipboard companions include a jaded dandy played by the comedian Jerrod Carmichael and a world-weary dowager played by Hanna Schygulla, long ago the jewel of the New German Cinema. Margaret Qualley turns up as a sort of Bella 2.0; Kathryn Hunter, the Weird Sister(s) of the recent “Tragedy of Macbeth,” as a wily procuress. Earlier, our heroine has walked under a Lisbon balcony in time to hear the great fado singer Carminho airing out her pipes.

Is it Lisbon, though, or the snow-globe Lisbon of an opium dream? Realism has no place in “Poor Things” – as conceived and constructed by production designers Shona Heath and James Price, the movie’s a hermetically sealed world as cooked up as anything in Dr. God’s lab. A tinker-toy fable, half magic lantern show, half sci-fi morality tale. The production’s craftwork conspires toward the off-kilter and surreal: Holly Waddington’s costumes are an idea of Victoriana from one parallel universe over, and Jerskin Fendrix’s score features delicate piano melodies that keep getting stretched and bent over unearthly scales. Robby Ryan’s cinematography borrows from the conjuror’s tricks of Georges Méliès at points, and under his boss’s urging he breaks out the fish-eye lens early and often. (I once wrote that many directors crib from the films of Stanley Kubrick but that Lanthimos was notable for stealing mostly the bad bits.)

With all that frippery, you’d think “Poor Things” would capsize like an over-frosted wedding cake. It doesn’t. It holds steady and true as Bella’s stations of the cross take her to Paris and beyond, through fleshly passion to greater compassion, and to a resolution that’s as satisfying as it is bonkers. Everyone here gives performances pitched to the outsized stature of their characters, but Stone does something bigger, weirder, and more attuned to an actor’s discovery of her gift and a woman’s discovery of herself – both of them in the context of a world and an industry run by men. Bella walks like a child and speaks like a child, but she comes to enjoy her body oblivious to censure and grows into her own heart and mind ungoverned by anything her society wants or expects. “Poor Things” is a hero’s journey jolted to life in a new frame, and somewhere, I’d like to think, Mary Shelley is laughing her ass off.

Comments? Please don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, feel free to pass it along to others.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be eternally grateful — here’s how.

You can give a paid Watch List gift subscription to your movie-mad friends —

Or refer friends to the Watch List and get credit for new subscribers. When you use the referral link below, or the “Share” button on any post, you'll:

- Get a 1 month comp for 3 referrals

- Get a 3 month comp for 5 referrals

- Get a 6 month comp for 25 referrals. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

There’s a leaderboard where you can track your shares. To learn more, check out Substack’s FAQ.