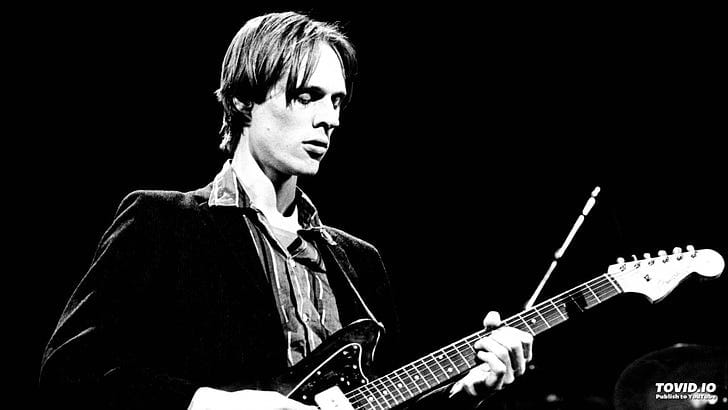

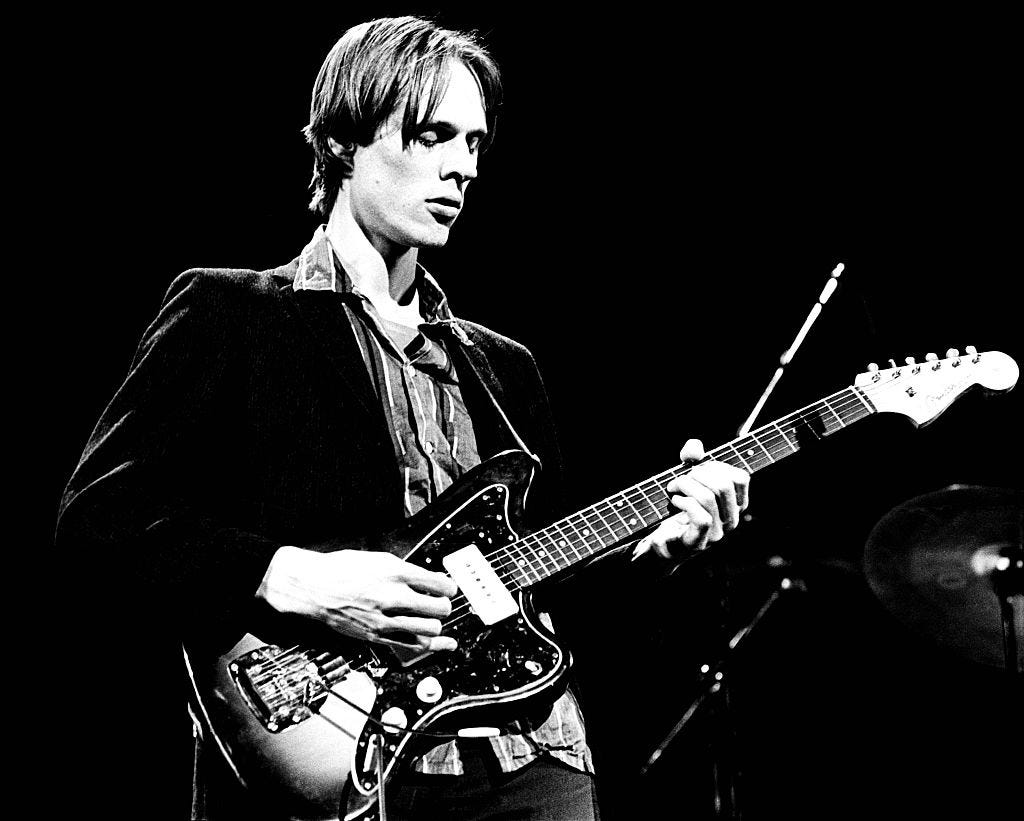

Tom Verlaine 1949-2023

One of rock's most mysterious figures drifts into the night.

To this week’s new subscribers: I usually write about movies and streaming options but occasionally about other cultural pursuits, including music. It’s a quiet week on the new film release front, I’m a little burned out after the Sundance Film Festival, and one of my heroes just died. So you’re hearing about him today. Later this week: A review of TV’s “Poker Face.” Back to movies next week. Thank you for your indulgence.

If you love music – popular music, the music that has come out during the timeline of your life – you may have a handful of bands or performers that you think of as “yours.” That define a particular place, time, or genre, or that feel like a secret the rest of the world never got around to. You found them early, you bought everything they recorded, you saw them whenever you could. Maybe you chased down rarities and bootlegs. They’re one of the pillars of your personal taste, a sonic and cultural constant that in some odd way has helped describe you to yourself. They’re your guys (even when they’re women).

Tom Verlaine was one of my guys. At various points in my life, he was the guy. I find it interesting that since his death this past Saturday at 73 – from a brief, undisclosed illness that is rumored to have been prostate cancer – he has been widely eulogized in the press and on social media and, in the process, has been introduced to many people for the first time. Patti Smith, who was with Verlaine from the beginning as both lover and fellow East Village misfit/mystic, has written a lyrically moving farewell in next week’s New Yorker that I imagine will make a lot of people sit up and head to Spotify. The New York Times has run two appreciations, a proper obituary and a listener’s guide. Musicians from Michael Stipe to Wilco’s Nels Cline to Flea have bowed low in grateful online obeisance. Yet so uninterested was this gaunt downtown martyr-saint in fame or even a career in the traditional music-industry sense that he spent a lifetime flying below the radar, where only other performers and/or devotees of New York rock and the outer limits of popular music heard the pinging of his guitar. Basically, he hung out at the Strand bookstore a lot and gigged when he felt like it.

It’s a gloss to say that Verlaine, on his own or with his band Television, was “influential” or “a musician’s musician,” although both are true. (The Canadian pop group Alvvays named a song on their most recent album “Tom Verlaine” a good half-century after the man picked up his first Fender Jazzmaster.) But in his musical restlessness and willingness to explore, his chasing rock transcendence at the cost of everything else, he informed and inspired many listeners who went on to make their own music, some of which became very popular. Still, even an act like The Strokes, who name-checked Verlaine and Television with regularity at the turn of the millennium, never actually sounded like him. Nobody did. That’s why some people, myself included, kept coming back. (If nothing else, he evoked for me a mythic New York moment that happened just before I got there — which is why it was so easy for me to romanticize it.)

Others stayed away, confused or turned off by the music’s defiantly rough edges. The band was a tough sell: I took a bunch of Boston buddies to an early-2000s Television gig that turned out to be an off night; they haven’t stopped razzing me about it since. Anyway, wasn’t Television supposed to be a punk act – the punk act, the group that talked Hilly Kristal into letting rockers take the stage at CBGB (named for Country, Bluegrass, and Blues) in the first place? Then how come they didn’t sound like the short sharp shock of the Ramones, or the retro irony of Blondie, or the art-school cool of Talking Heads? If the Grateful Dead is considered the primordial jam band, then Television was the style’s unheralded second iteration, trading acid bliss for urban angst, sunny San Francisco vibes for midnight Manhattan urgency. Verlaine’s and Richard Lloyd’s twinned guitars soared around each other like fighter planes, propelled by Fred Smith’s Motown bass lines and Billy Ficca’s drums – as fine a rhythm section as has ever played a New York club – and if the songs could run long on vinyl, they were transformed in concert into living things that could lift you straight into a noisy, ungentrified heaven. On record, Verlaine’s signature song “Marquee Moon” was an un-punkish 10 minutes and 47 seconds. I have bootleg recordings where it surges past the 20-minute mark and heads straight toward the horizon.

Yeah, I collected bootlegs – I and a small cohort of others, mostly guys of a similar fraying age, who communicated through an online Television fan site and newsgroup and who traded live recordings by mail, a devotional priesthood separated by state borders and international time zones. The newsgroup was mostly silent in recent years, since Verlaine didn’t gig much or record any, either solo or with the latter-day version of Television (minus Lloyd and plus second guitarist Jimmy Rip). Since Saturday, though, we’ve been coming out of the woodwork, old men at a digital wake, trading obit links and talking about the first times we heard him. (The newsgroup moderator Phil Obbard, a good friend, has a lovely appreciation here.)

My own first time would have been 1979, when my Hoboken apartment-mate Gerard brought home Verlaine’s first solo album and I tried to connect its sounds with anything I’d ever encountered before. The singing first: With a high tenor that is best described as “strangled,” Verlaine made Bob Dylan sound like Pavarotti, and for many listeners that was the exit door right there. The mistake they made – the mistake most people make about Tom Verlaine – is that he didn’t actually sing with his voice. He sang with his guitar.

But even the way he did that was challenging and, once you’d acclimated to the atmosphere, exhilarating. A ballad like the first solo album’s “Last Night” with its ringing guitar solos, inhabited a known blues-rock universe familiar to me from Santana and Mick Taylor’s work with the Rolling Stones. It was pretty; I liked it. But the escalating arpeggiated ecstasy of the closing cut, “Breakin’ in My Heart” excited me, like your first view of a new planet hoving into view through a spaceship window.

I subsequently backtracked to the first two Television albums, recorded before the band imploded: “Marquee Moon” (1977) and “Adventure” (1978). The shock for me (and the bait on the hook) was that I still couldn’t square them with anything in rock or pop music up until then. Nothing triangulated. The guitars especially fit no known quadrant of radio or turntable play. This wasn’t pop, and it wasn’t blues. It wasn’t Jethro Tull or Steely Dan, and it certainly wasn’t metal. It lacked the cocksmanship of post-Hendrix axe heroics, although it shared Jimi’s taste for exploration. I had yet to learn that Verlaine’s musical influences encompassed everything from the free jazz of Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler to the garage rock of The Count Five, whose 1966 gutbucket classic “Psychotic Reaction” he often played in concert. Tom’s playing could be savage and it could be unbearably tender, sometimes in the same song – sometimes in the same stanza.

Ironically, Verlaine was on record as saying he thought of “Marquee Moon” as a pop album, which seemed charmingly perverse. To me, his songs posed an intriguing question, which was: How far can you atomize sound while staying within the most tenuous framework of verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-verse-chorus? As far as I was concerned, that was more punk than anything the Ramones or the Sex Pistols could come up with.

Verlaine put out nine solo albums, only the first five of which are available on Spotify or other streaming music platforms. (Missing is 1992’s evocative instrumental workout “Warm and Cool” – a taste of the musician’s side hustle scoring silent films.) “Dreamtime” (1981) is probably his strongest record, but it’s not for the faint of heart: Beatific power-chord rock with inventive song structures, beguiling lyrics, and volume set on stun. “Flash Light,” from 1987, may be the most appealing to newcomers; despite that mechanical drum thwap that blights most of the decade’s records, Verlaine sounds engaged, upbeat, curious, and the songs linger in your brain like pop rocks. And in the words to “The Funniest Thing,” he comes as close to a philosophy of life, art, career, and music as he ever would come: “I think about it all of the time/but I don’t want to talk much about it.”

And then he uncorks a guitar solo that makes everything else disappear.

I stress, again, that the studio recordings mostly serve as templates for live performances that are Verlaine’s and Television’s real legacy. (That this body of work is floating out there on cassette tapes and MP3s is another aspect of the Tom Verlaine mystery – a catalog that Borges might have envied, immense and unheard.) You can hear some of what they wrought on the handful of live albums released over the years: “The Blow Up,” recorded at CBGB in 1978, has the band at their squalling early best, with a version of Dylan’s “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” that is both sloppy and majestic. “Live at the Academy, 1992” (available on Tidal and iTunes only) is from the tour following the band’s early-90s reunion; the second track, “1880 Or So,” offers a precise demonstration of Television’s two-guitar approach, Richard Lloyd soloing first with fiery proficiency within a traditional rock framework and then Verlaine heading toward outer space on the second solo.

On a YouTube playlist I’ve created — accessible here — I’ve tacked on a version of “Marquee Moon” I taped at New York’s long-vanished Ritz nightclub in 1987. Is this my favorite version of the song because Verlaine (playing with the band he used for his own albums) lets loose a long, intensely liquid guitar solo in which he seems to re-invent sound itself? Or is it simply because I was there?

Yes.

Rest in uncontainable peace, Tom.

Thoughts? Don’t hesitate to weigh in.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to pass it along to friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how.