Fred Smith: Ace of Bass

Farewell to the heartbeat of a legendary rock band.

The first thing anyone heard by Television outside of downtown New York was Fred Smith's bass. Dum-dum-dum... Dum-dum-DUM: The descending opening notes of "Little Johnny Jewel" take us down a crumbling set of steps off The Bowery into the darkness of a dive bar where a crew of gaunt nobodies are playing as if their lives depend on it. The double-sided single, released on Ork Records in October of 1975, was a sign that something was happening below 14th Street, and most people had no idea what it was.

As with all of Television's songs, "Little Johnny Jewel" truly came alive on a concert stage, and if the band's two guitarists, Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd, hogged all the attention, Smith's bass lines and Billy Ficca's drumming did artful, overlooked things in the background. No, background is the wrong word: Like all good rhythm sections and better than most, Smith and Ficca laid down the foundation upon which Verlaine and Lloyd could build a different edifice every night. They were the tarmac from which twin fighter jets could take off and entwine their smoke trails in the sky. The whole group glowered with style, as is evident from the cover of their first album, "Marquee Moon," a Robert Mapplethorpe photo run through an Astor Place print shop copier. But as with all great bass players, you couldn't really appreciate Smith until you paid attention to the details and design of the anchor which which he grounded the group.

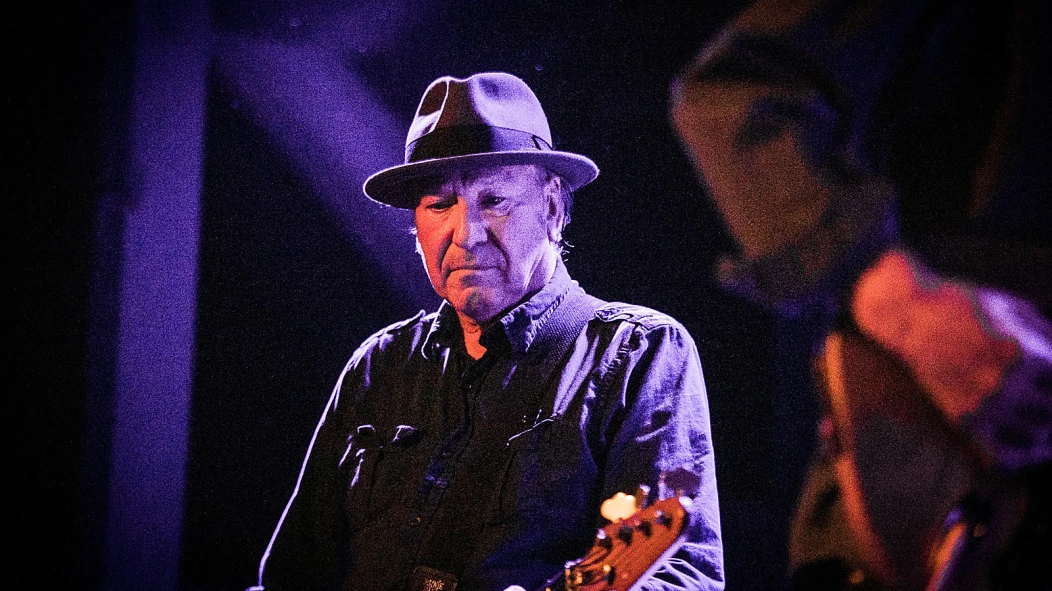

The news of Smith's passing at 77 hit the Interwebs yesterday, and those of us who cared felt a little older and sadder. Now half of Television is gone, Verlaine having died in January 2023. Richard Lloyd is still out there touring – feet first off a nightclub stage is the way he'll go – and Billy Ficca is doing whatever drummers do when they're not in a band. But if Verlaine's death was the end of an era, the loss of Smith is more like a piece of bedrock carried away.

The popular image of a bass player is a pillar of stolidity, expressionless and capable: Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones with his Deputy Droopalong face, or The Who's John Entwistle, of whom it was once said that he watched the aggro-destructo antics of Messrs Townsend, Daltrey and Moon, "and just stood there, as if he'd seen it done better." On the other end of the spectrum is someone like Paul McCartney, who turned the bass into a contrapuntal second guitar, or Bootsy Collins way out there on the interplanetary rim, or Tina Weymouth, a tweety-bird of pure rock and roll joy. But Fred Smith fit the first cliche just fine, showed up, did his job and kept his lip zipped, at least onstage. (And, anyway, who would want to wander into the acrimonious field of fire between Verlaine and Lloyd?)

Yet if you listen closely to his playing, it's a steady pulse only when it needs to be. At other times, Smith's bass lines are a form of anarchy in their own right, somehow stable enough to allow a greater anarchy to find its center. Smith was brought into the band in large part to not be a glory hound, since he replaced Richard Hell, Verlaine's old boarding school buddy and fellow avant prankster who'd been bounced from the band (or quit; it depends on who's talking) because looking the part of a proto-punk rocker was always more important to him than learning to play an instrument. (Also: Hell wanted the band to play his songs as well as Verlaine's; Smith had no such designs.) The bassist left the nascent Blondie, then called the Stilettoes, to join the group, which seemed like a very smart thing to do in 1975, since Television was at that point the more going concern. (Debbie Harry was by all accounts pissed.) Richard Lloyd has said that Smith gave the band "a tonal centre it hadn't had [when Hell was in the group]. Fred became the stable element that ... let the gears not look like a watch that had sprung but a very interesting group of gears moving."

Did Smith regret the decision? If he did, he didn't say, and it may be that he shared Verlaine's vision that the whole point of being in a band was to discover the music in the moment of playing it, live and before an audience rather than behind the glass wall of a recording studio.

So he was loyal, as far as I can tell, playing on much of Verlaine's solo work –

– and Richard Lloyd's –

– and gigging with the Roches and the Fleshtones until Television reunited in 1992 on record and in concert, where they played on and off for 30 more years until Verlaine's final illness. If you caught the band during that span, you'd hear songs that never made it to an album – long, long jams like "Persia," a number that Fred kept from floating off into the ether with a crawling king snake of a bass riff.

What did he do between gigs? Among other things, Smith and his wife, artist Paula Cereghino, started making wine in their East Village apartment in 1999, a small business that eventually moved upstate to become Cereghino Smith, purveyors of fine artisanal wines like Rock 'n' Roll Red and Eaten By Bears. He seems to have ended his days a small-batch country vintner – a far and well-earned distance from the gob-splattered stage of CBGB.

So maybe order a bottle or two and pour one out for Fred. And while you're at it, pour one out for all those players whose music we love and whose names we all too rarely know.

Feel free to leave a comment or add to someone else's.

Please forward this to friends! And if you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be very grateful — here’s how.