Flashback: "The Friends of Eddie Coyle"

Ahead of tonight's Zoom talk, I ask: Is this the best Boston crime movie evah?

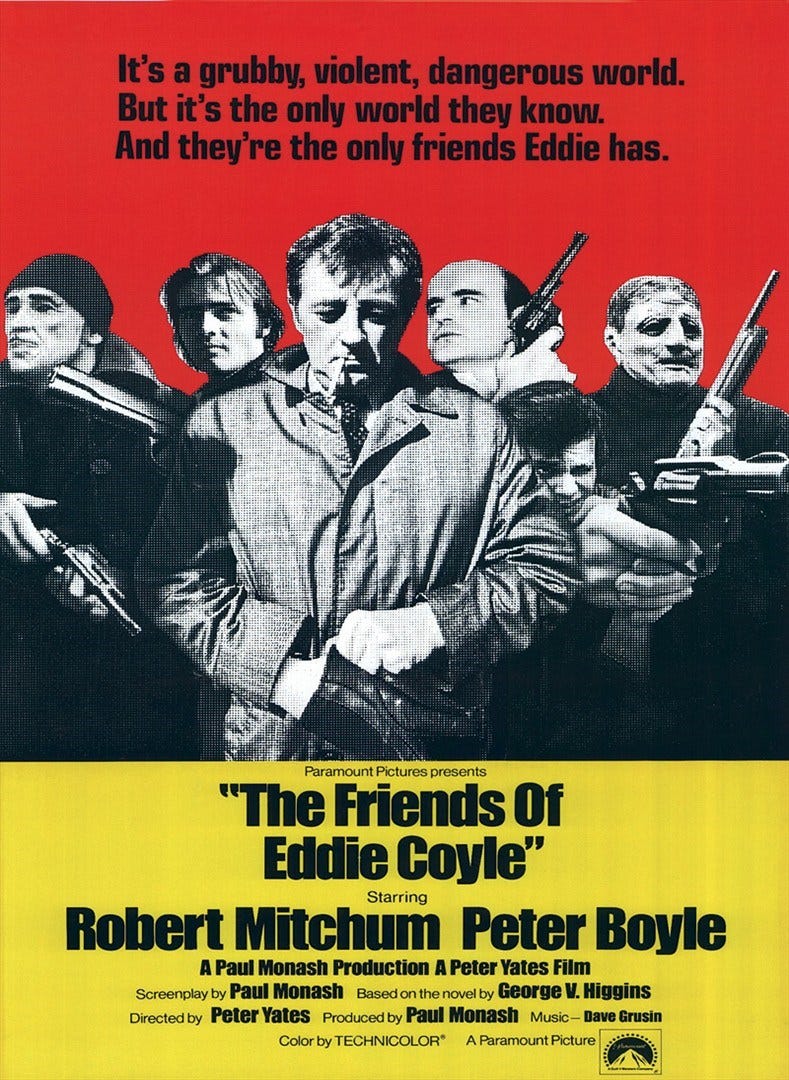

I had the dark pleasure this weekend of rewatching “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” (1973, streaming on Kanopy and for rent on Amazon, Apple TV, and elsewhere, **** stars out of ****). It’s the very first Boston crime movie and, in the opinion of many, myself included, still the best. I’m leading a talk about the film tonight in a Zoom event for the Massachusetts Historical Society – you can register for it here – organized by the Society’s Director of Programs Gavin Kleepsie, who is in agreement with me that the Peter Yates movie captures something grim and essential about our fair city’s criminal element that not one of the belated follow-ups has managed to replicate. That something is the blunt, uninflected poetry of defeatism, baked into people who have grown up poor between the rock of Puritan piety and the hard place of Catholic guilt. Who’ve learned to take what they can get or grab and still assume they’ll be punished for it, either by the law or by their own. That title is a sigh of irony, because Eddie Coyle has no friends, and neither does anyone else here.

I say it’s the first Boston crime movie because no one had really put “Boston” and “crime” together in the same sentence before George V. Higgins, a B.C. Law graduate and assistant US Attorney, wrote the 1970 novel “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” – the first of 27 novels written before his untimely death at 59 in 1999 – and before the British-born Yates made it into a 1973 film. The Brinks Robbery of 1950 still held a place in the cultural memory, but that was it; Boston to the rest of the country still meant Paul Revere and Henry Cabot Lodge, a WASP power structure and an Irish Catholic archdiocese. Institutions and great men, not the working class of Southie and Charlestown (and certainly not the city’s Black population in Roxbury). Higgins wrote his book four years before court-ordered school desegregation and the ensuing busing crisis debuted a new figure on the national stage: The aggrieved Boston mook, with an irreducible accent and a long, long list of grievances, a lot of them justified.

That figure is now a stereotype, hammered into classist cliché by a generation of Hollywood movies: “The Departed,” “Mystic River,” “Gone, Baby, Gone,” “The Town.” I could go on, I will go on: “The Fighter” (Lowell, but close enough), “Monument Avenue,” “Black Mass,” all the way down to the woeful self-parody of “Boondock Saints.” “Boston Accent,” the fake trailer created for “Late Night with Seth Meyers” in 2016, was effectively the coffin nail for a genre that was already rigor mortis. Who to blame for the overkill? Possibly Dennis Lehane, whose best-selling novels resurrected the world Higgins created in letter and spirit and who simply had better timing in terms of Hollywood and the popular culture. But I think even Lehane would agree that there would be no “Mystic River” or “Gone, Baby, Gone” without “The Friends of Eddie Coyle.” Higgins broke the ground, and he did it by simply listening to the thugs and thieves and hit men and gunrunners he helped put behind bars.

To read Higgins is to steep oneself in the glory of brute regional dialogue, shorn of anything but the most functional prose. His books plunge us into conversations in bars, in diners, in cars bucketing down Morrissey Boulevard in Dorchester, forcing us to navigate on our own. Who are these people? What are they planning? Who are they ratting on and to whom are they ratting? It’s all performative improvisation, because no one is to be trusted – certainly not your “friends” – and that makes the men (they’re all men) irritated and not a little desperate. It also makes reading Higgins almost indecently funny, because he preserves the ornate contortions of the way these people speak with something akin to love, never condescending to his characters but acknowledging that they’re murderous creeps who can be exceptionally good at talking themselves into failure.

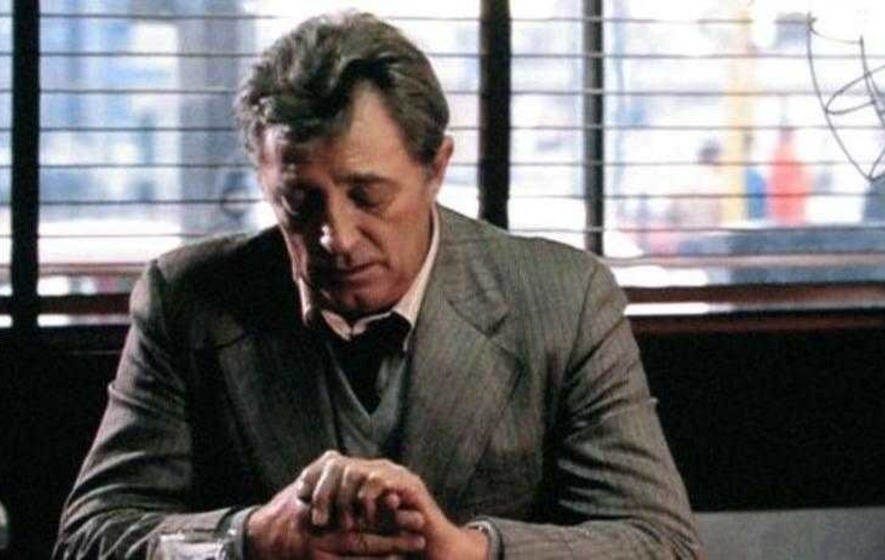

Eddie Coyle, for instance. He’s a weary 50-something low-level hood, a middleman providing guns for some guys he knows who are into robbing banks out in the suburbs. Eddie has a sentencing coming up in New Hampshire – he was caught driving 200 cases of stolen Canadian Club – and he’s so anxious to stay out of prison he’s maybe willing to drop a dime on someone. Maybe the guy who sells him the guns, a young punk named Jackie Brown, and if you think Quentin Tarantino has a thing for “The Friends of Eddie Coyle,” you’re right.

In the book, Coyle is a “stocky man” with no other descriptors. We’re invited to fill in his features for ourselves from the police lineup of our imagination. In Yates’ movie, he’s played by Robert Mitchum in one of that great actor’s finest and most subtle performances. The rest of the cast does good work, too – Peter Boyle as a traitorous bartender, Richard Jordan as a studiously hip police detective, Alex “Moe Greene” Rocco as one of the robbers – but next to Mitchum you feel the force of performance with them. Mitchum just is. The one-time hero of 1940s film noirs knows he’s working with shades of gray here and that there are no heroes and not really any tough guys, only the successful and the dead. Even the actor’s Boston accent is worn lightly, a windbreaker rather than a heavy winter coat.

Mitchum wanted to meet Whitey Bulger during the “Eddie Coyle” shoot, but Higgins advised against it. The star did meet with Howie Winter, a rival Boston gangster; there’s a boozy photo of the two with a handful of miscellaneous goodfellas and Alex Rocco (being kissed by Winter), who was born Alessandro Petricone in Somerville and had a rap sheet that included suspicion of murder before he did time, moved to California, and became an actor.

It’s actually a wonder that “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” got made at all, considering how hostile and violent the mob-run Teamsters could be to film crews from out of town. But then, “Eddie Coyle” is about those guys. On the commentary track of the DVD, director Yates talks about having an impromptu consultation with one of the on-set drivers about the proper way to carry out a hit. The man said he’d “heard” about what to do and what not to do, but as he gave more and more details, Yates realized he was working from firsthand knowledge.

For anyone raised in these parts, what makes the original novel and all of Higgins’ work so special is the way he roots everything in geographical specifics. In “Cogan’s Trade,” a 1974 novel turned into a pretty good 2012 Brad Pitt movie, “Killing Them Softly,” a beating is administered not just in a nighttime parking lot but in the parking lot of the old Stearns department store behind Route 9 in Chestnut Hill. (It’s now a Shake Shack.) To read the beginning of Chapter 17 of “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” is to breathe the particular misery of trying to get anywhere in Boston:

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when published“Jackie Brown got caught in traffic in Watertown. He escaped briefly and got caught again in Newton. On 128, he eased the Roadrunner into a three-lane pack of first-shift electronic workers heading home and settled down to an unobtrusive fifty miles an hour. There was a three-car accident in Needham, and he waited patiently in the center lane, surrounded by a thousand cars, while the sun declined and the evening began.”

The movie shoots the prose with unadorned directness, honors the locations (the old Boston Bowl in Dorchester, the Gahden), and retains the dialogue in all its arcane profaneness. Yates says on the commentary track that anytime they tried to come up with new dialogue, it sounded fake and flat – the actors couldn’t work with it. What Higgins wrote – what Higgins heard – was all that was necessary. The scene below, Eddie playing tough to the gunrunner to get what he wants, is taken directly from the page, and it is glorious.

Every Boston crime movie that came after “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” has sounded vaguely fraudulent in comparison, even the good ones like “Gone, Baby, Gone.” It’s not that the actors can’t get the accents right (and they can’t). It’s that the melodrama that provides Hollywood movies with their forward momentum has no place in this world of animal instinct and survivalism. “Goodfellas” is the quintessential New York mob movie because it’s about the showiness and the swagger. “The Friends of Eddie Coyle” is Boston’s best crime movie because it knows that none of those things will ever buy you an edge, from the law, from your friends, or from God.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.