"Exile on Main Street" Turns 50

The Stones' masterpiece may be the only time they actually meant it.

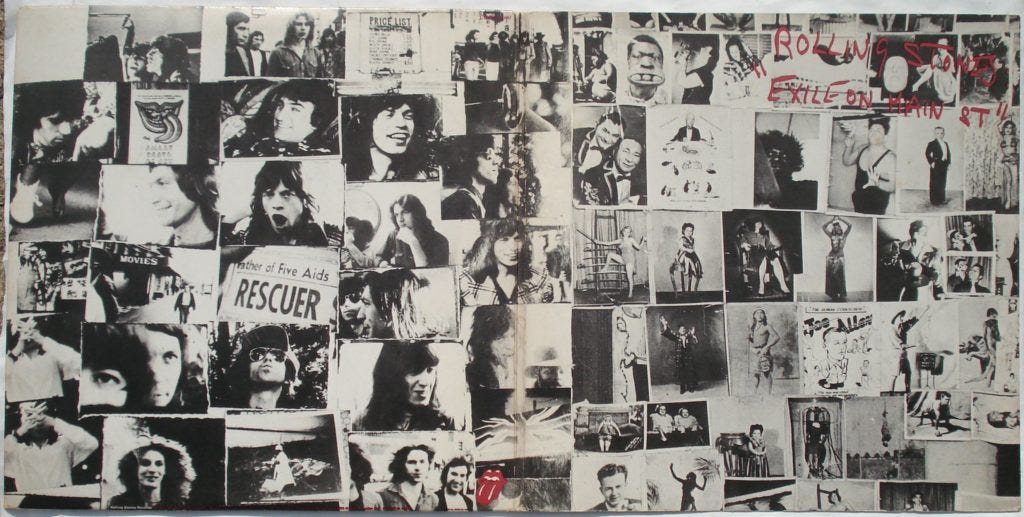

Fifty years ago tomorrow, the Rolling Stones released the double album “Exile on Main Street.” It was the best thing they ever did. It was also unlike anything else they ever did, before or after, and to this day it confuses some Stones fans and first-time listeners. Honestly, the first time I heard it, back in 1972, I thought it was sludge – a murky goulash of tracks that were impossible to differentiate from each other. Reviews were mixed. Hardcore fans were puzzled and casual fans like me turned up “Tumbling Dice” whenever it came on the radio and ignored the rest.

It wasn’t until I was in college several years later that I got it, during a long overnight drive where “Exile” was the only cassette in a friend’s car. As we bumped down Interstate 91 from New Hampshire to New York City, the songs began to disentangle themselves into their constituent melodies, riffs, and genres: Gospel-inflected ring shouts (“I Just Want to See His Face”), country love songs (“Sweet Virginia”) and laments (“Torn and Frayed”), blues rave-ups (“Stop Breaking Down”), guitar boogie (“Shake Your Hips”), horn-driven shuffles (“Ventilator Blues”), pile-driving declarations of love and lust (“Loving Cup”), straight-up rockers (“Rip This Joint”) and heartfelt unburdenings of the soul (“Let It Loose”). “Exile on Main Street” is a great midnight-to-dawn record in large part because those are the hours in which it was recorded.

By the time we arrived in Manhattan, I’d come to understand that it’s best not to think of the album as a collection of songs at all but as a towering work of atmosphere. A record soaked in exhaustion and decadence and a love for a specific kind of music that had finally sunk into the musicians’ bones. A half century on, “Exile” isn’t just the one record where the Rolling Stones dropped the posturing and became what they’d only pretended to be (quite expertly) up to that point. It’s the album where the eternal Classic Rock issue of white musicians appropriating Black musical forms to great cultural cachet and profit finally became moot, or as moot as it ever would get. Which makes it as relevant as ever and a fascinating point on the timeline from minstrelsy through Elvis to Eminem and beyond.

Elvis, of course, was very vocal about supporting the Black artists who influenced him, and Eminem has long since been accepted by the gatekeepers of hip-hop. Along with the Animals and Eric Clapton, the Rolling Stones were in the wing of the 1960s British Invasion that fetishized American blues and R&B (as opposed to more pop-oriented groups like the Who, the Kinks, Herman’s Hermits, et al.; the Beatles just drew on everything). This could turn to shock upon touring the American South and seeing the racist reality of where the music came from, as Eric Burdon discovered when (per his autobiography) the Animals were run out of Meridian, Mississippi, in the mid-1960s for not playing White music.

The Stones especially turned their love of Black music, from their name on down, into an integral aspect of their rebellious image, drawing on the anger of the underdog with few of the attendant risks. On the early records, their taste in cover songs was impeccable, their originals ingenious, their misogyny daring rather than cruel. They promoted themselves as the anti-Beatles – the line was that the Fab Four wanted to hold your hand while the Stones wanted to burn down your house – and much of the power of the pose came from their insistence on real rock ’n’ roll, which was nasty and sexy and rude and exciting. And Black. They made that work up until 1968’s “Beggars Banquet,” at which point (and with the assistance of producer Jimmy Miller), they took a turn for the legendary, with a more hard-driving, bottom-heavy sound and songs like “Street Fighting Man” and “Sympathy for the Devil” that seemed as prescient in their implied social commentary as anything by Dylan.

The four records released in those four years – “Beggars Banquet,” “Let It Bleed” (1969), “Sticky Fingers” (1971), and “Exile on Main Street” – represent one of the all-time great album runs, but they didn’t resolve the issue of how much Mick and Keith took from American music – Black or White -- because they loved it and how much they took because it just felt cool. Some of Mick’s “country” singing (“Country Honk,” “Dear Doctor”) is embarrassing to listen to today, just as some of their covers of blues (“You Gotta Move”) or R&B (“Let It Bleed”) sound awfully forced.

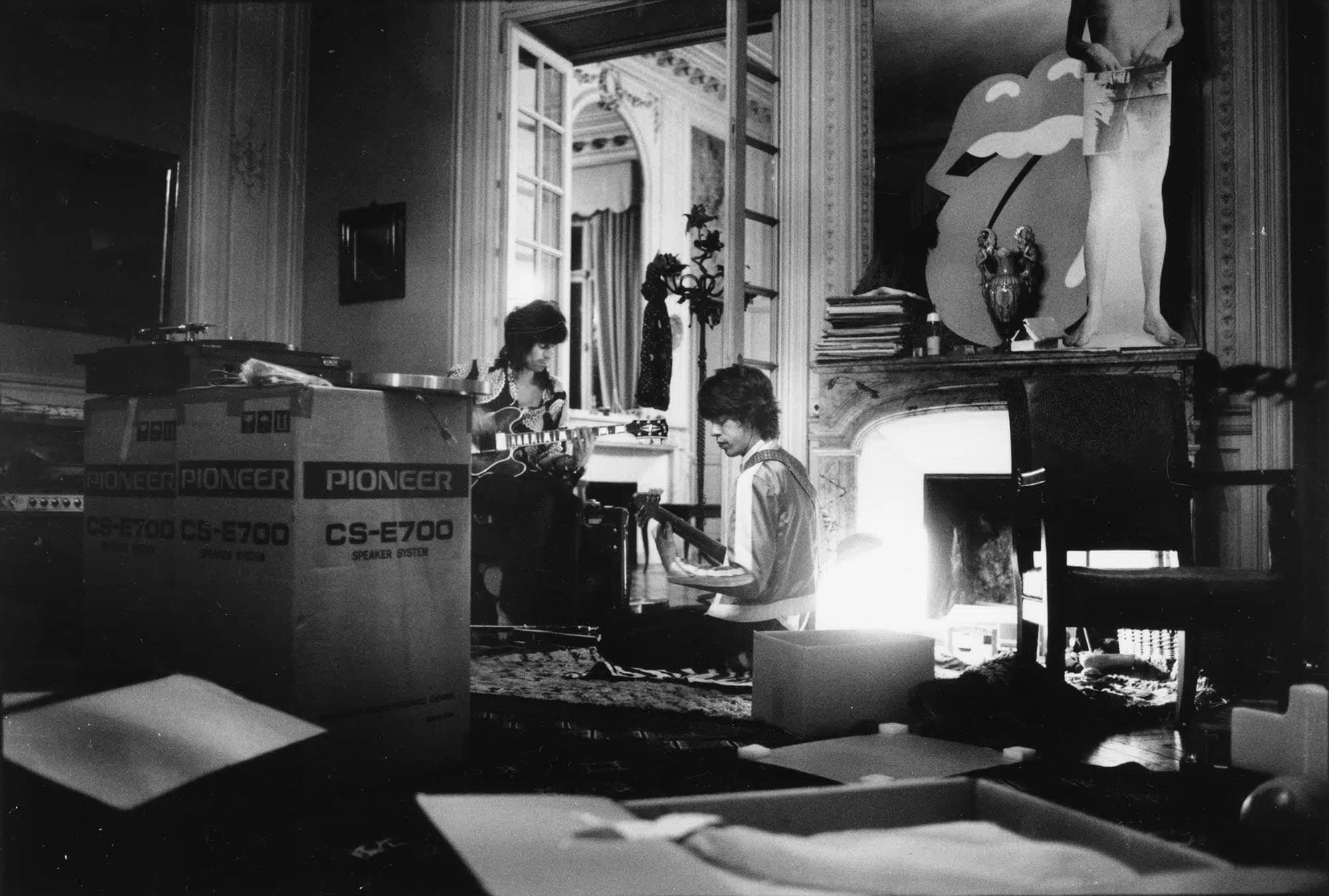

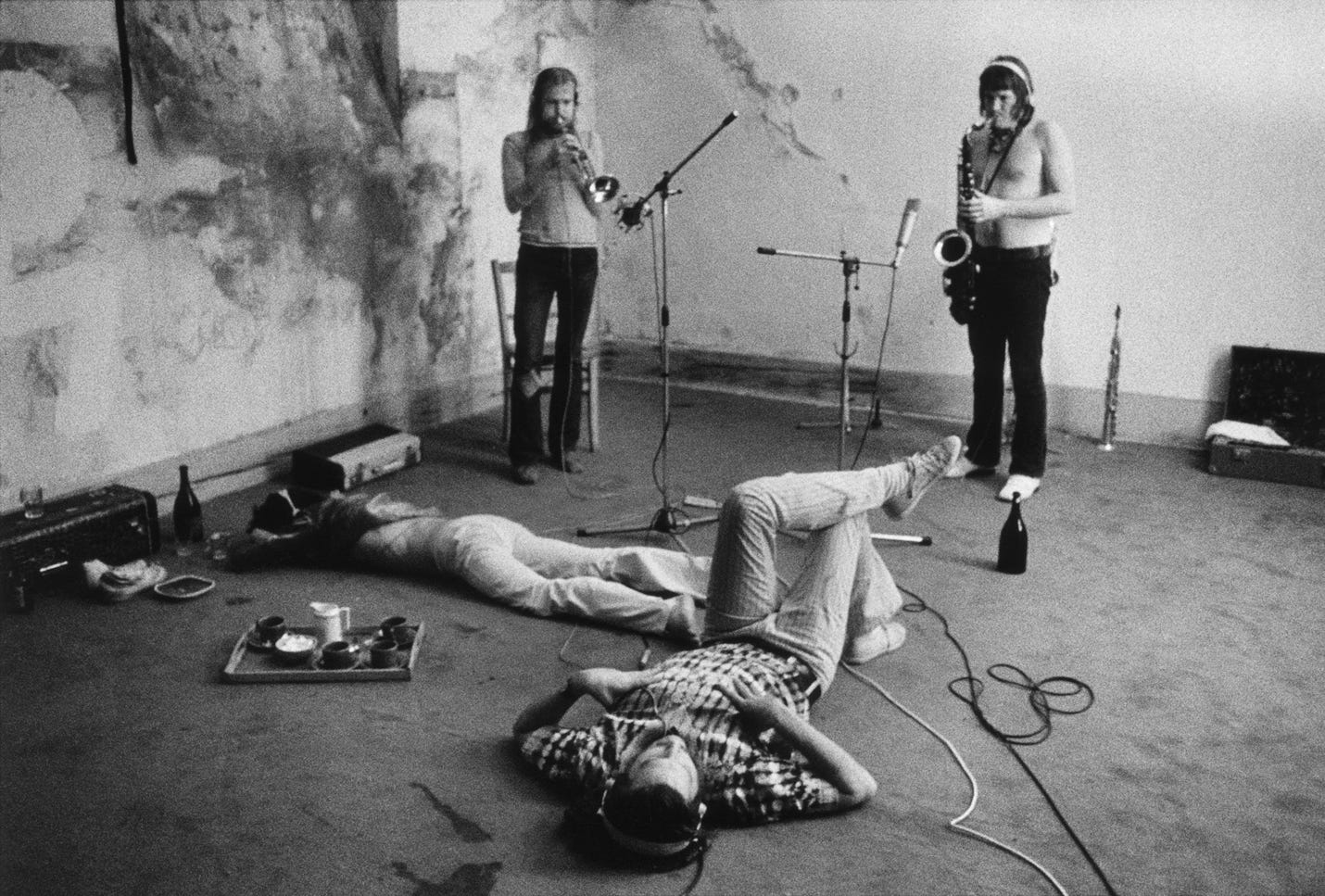

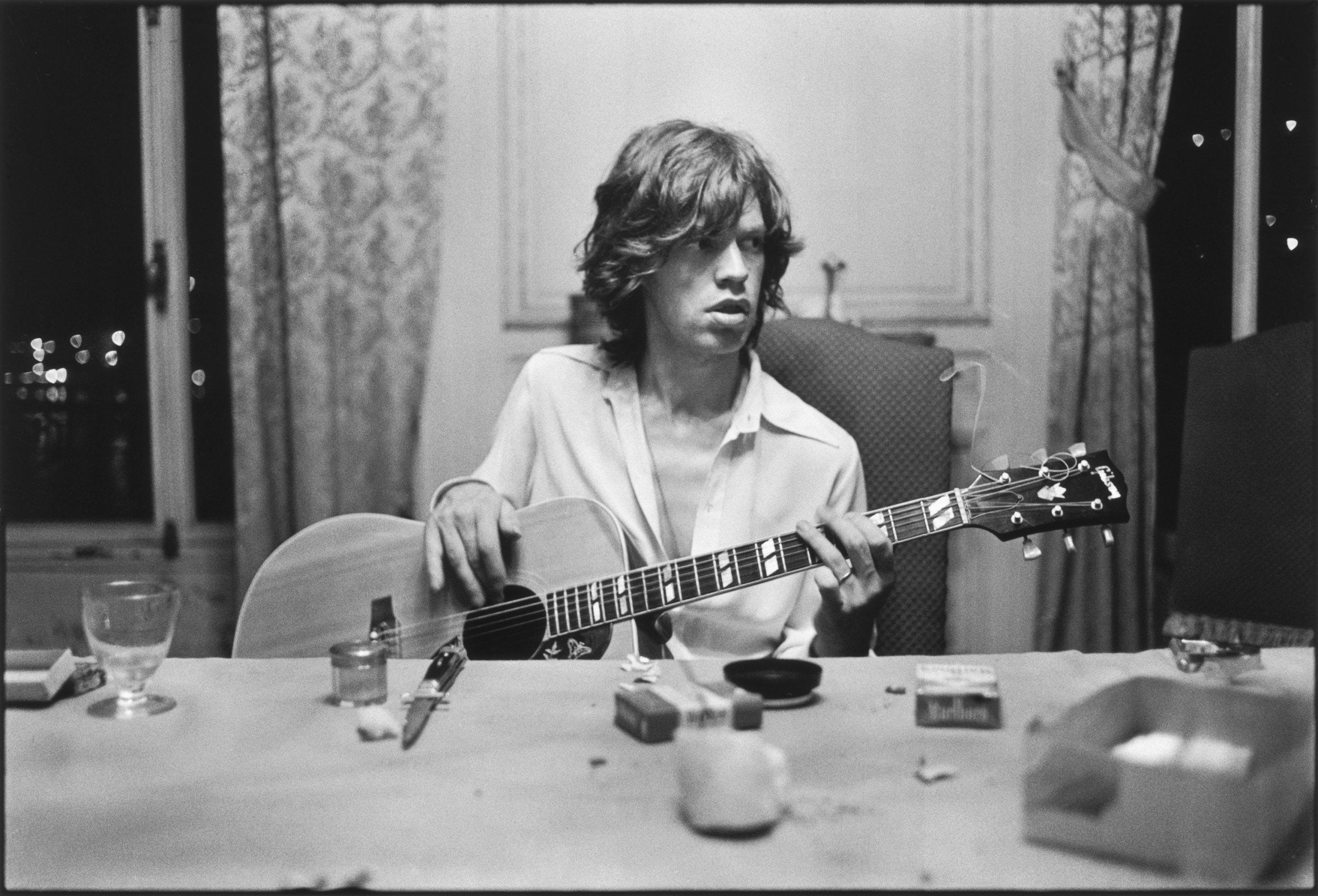

With “Exile,” that changed. Recorded over several sweltering months in 1971 in Keith Richards’ French villa Nellcôte, it’s Keith’s album much more than it’s Mick’s, and the irony is that Keef was at his most strung-out on drugs at the time. If Jagger was the theorist and agent provocateur of the Stones, Richards was the keeper of the musical flame, and the Nellcôte sessions were steeped in a love of the groove, with very little demarcation between work and play. Songs grew out of jams that seemed to be going nowhere and then suddenly came together with outrageous force.

The result is the group’s least conceptualized, least thought-out piece of work. “Exile on Main Street” is a record not composed but simply played. It’s such an anti-concept album that it becomes a concept album by default: The concept is the riff, the groove, the pocket. Charlie Watts’ backbeat and pianist Nicky Hopkins’ hammering eighth notes, Bobby Keys and Jim Price conjuring horn charts from the 30s, 40s, R&B 50s, and Keith’s rhythm chords resounding like a rusty Valhalla. With some exceptions (“Stop Breaking Down”), Mick Taylor’s hot-shit British blues-boy guitar was kept on a leash, and while his gentle eloquence is missed, this is not a record about the solo.

As such, Mick is buried under the murk, his vocals haunted by their own “ghost tracks,” early temp versions laid down for guidance but still heard as a shadow version in the mix. No wonder he hated the record and seemed ever baffled by its standing. Jagger took charge during the later L.A. sessions that added backing vocals and overdubs, and he apparently was inspired by a visit to the church where Aretha Franklin was recording “Amazing Grace” to infuse cuts like “Let It Loose” and “Loving Cup” with a rich gospel sway. But he never came around. In 1971, before “Exile” even came out, he told a reporter, “The new album’s very rock & roll, and it’s good, [but] I’m very bored with rock & roll.” By 2003, Jagger was saying “Generally I think it sounds lousy … I had to finish the whole record myself, because otherwise there were just these drunks and junkies. Of course, I’m ultimately responsible for it, but it's really not good and there's no concerted effort or intention."

I beg to differ, as do a lot of people – as does posterity. But it makes sense. Like a lot of other great pop musicians of his time – David Bowie and Ray Davies of the Kinks spring to mind – Mick Jagger liked to play roles and keep audiences guessing about what was real and what was an act. Keith Richards, by contrast, just liked to mean it, and by 1971 he was too spent and too wasted to do anything but mean it. “Exile on Main Street” is the greatest thing the Rolling Stones ever did because, after so many years of mastering the music and playing canny, ironic mind-games with their listeners, the games were overtaken by the mastery. This was no longer somebody else’s music. It was finally and fully theirs. They’d never get there again.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the discussions, here’s how:

If you’re already a paying subscriber, I thank you for your generous support.