Bud Cort 1948-2026

What the star of "Harold and Maude" once meant to the author's younger self.

Bud Cort, the star of "Harold and Maude," died Wednesday. He was 77. I've been writing a lot of In Memoriams lately, but this one's more personal than most. Probably too personal, but what the hell, it's my newsletter. Proceed with caution.

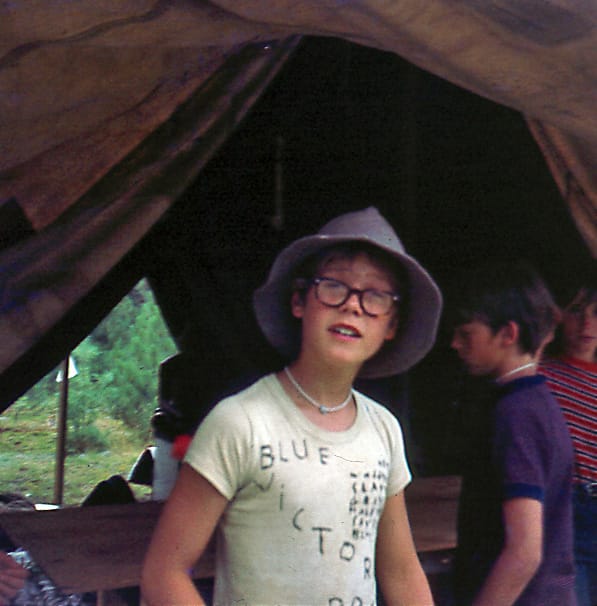

The people in movies serve us as both mirrors and models – templates for who we want to be, who we think we are and, every so often, who we might actually be. Bud Cort came into my life at a particular juncture, when I was 13 and had wandered alone into a downtown Boston movie theater that was playing "Brewster McCloud," the 1970 Robert Altman film in which Cort is cast as an owlish young man who lives in a bomb shelter beneath the Houston Astrodome, where he busies himself building wings with which to fly away. The movie is notable for being Altman's follow-up to his breakthrough success “M*A*S*H*,” for introducing Shelley Duvall to the world as a kewpie-doll Astrodome tour guide, and for briefly torpedoing the director's career. None of that mattered to me; I just knew I'd never seen anything like "Brewster McCloud" before and had also never seen someone who looked like me in a film – even more discombobulating, looked like how I felt.

I was going to movies by myself a lot just then. My father had died three years earlier, my mother was busy working to keep us clothed and fed, my older sisters were negotiating high school and college respectively. I found myself staying up late to watch old black & white movies on TV or hopping on the D line to go downtown to the city's mouldering movie palaces, most of them owned by a local exhibition mogul named Ben Sack. (One of the theaters was named for his son, Gary. Who goes to see a movie at The Gary? Well, I did.)

Movies were becoming my bomb shelter, in other words, in ways that almost certainly stunted my growth but ultimately gave me a career, or at least something to do until the credits roll. And "Brewster McCloud" was the first evidence I had that movies could be about anything at all – could break the rules and make up new ones, or poke you in the ribs with in-jokes. (Yes, that's Margaret Hamilton, the Wicked Witch of "The Wizard of Oz," as an elderly dowager, and, yes, those are the ruby slippers on her feet when she's found dead late in the movie). I didn't know what to make of it. I can't even tell you now whether I liked it. But I saw in Bud Cort – naive, bespectacled, hapless Bud Cort – someone who looked unnervingly familiar.

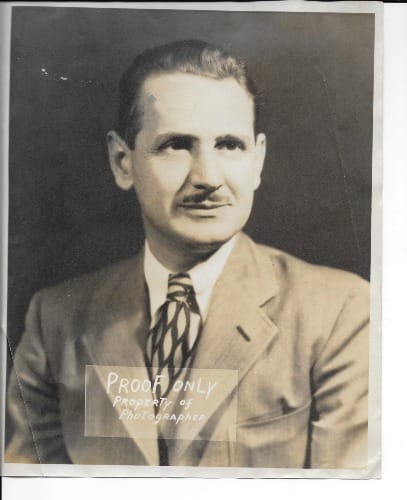

It was around this time that I also discovered the Marx Brothers, after my mother told me to stay up and catch "Duck Soup," which she said had been one of my father's favorite movies. I fell hard and especially hard for Groucho, who possessed the chutzpah I lacked and who vanquished all comers with a relentless firehose of language and absurdity.

For reasons that are obvious to me now but were invisible then, I conflated him in my head with my dad, who was also funny and outgoing and impenetrable. My father had me late in his life, when he was 47, and for me and my sisters he was a figure from an earlier world – a black & white planet of cocktail shakers and cufflinks and repartee. He even had a suit with tails; I never saw him wear it, but it hinted at late-night parties with balconies overlooking formal gardens.

Groucho wore a coat with tails, too, and I took that as part of his necessary armor, along with the cigar, the fake moustache, and the logorrhea. In my embarrassing adolescent film-geek enthusiasm, I took up the armor too, and wore a long brown trench coat for the entirety of my ninth-grade year, scuttling through the school halls in an imitation of Groucho's crabwalk while my peers were off sneaking into "The Exorcist." The schtick marked me only as one strange, sad kid, and while I cringe at the memory of that younger self, it was clear even then that Groucho was only on the outside. Inside, where no one could see him, was Brewster.

Or Harold. Bud Cort was and remains most famous for the role he played a year after "Brewster McCloud": Harold the disaffected teenager of the beloved cult classic "Harold and Maude" (1971) – spoiled scion, performer of elaborate fake suicides and lover of the elderly Holocaust survivor Maude (Ruth Gordon), herself one of the earliest (and oldest) Manic Pixie Dream Girls of modern cinema. Directed by Hal Ashby, the film was a flop upon release but caught on in the revival houses that had sprung up in major cities of the early '70s, playing endlessly to audiences that came for multiple viewings and brought their friends, who then came for multiple viewings and brought their friends. I must have seen "Harold and Maude" ten or twelve times over the two years it played at the Allston Cinema, and the difference between those screenings and "Brewster McCloud" was that I was no longer alone in the theater or in feeling that Bud Cort was my representative up there on the screen, his soft, unblinking eyes taking in the disaster of life and treating each day as a funeral until Maude jolts him out of his black suit and back into the land of the living.

Is the movie corny? God, yes. Obvious, sentimental, subtle as a ball peen hammer? Yes, yes and yes. "Harold and Maude" hasn't aged well (unless one looks at it through the eyes of one's younger self, which everything in our culture urges one to do), but that's okay, because I haven't aged all that well myself, and I bet you haven't either. Bud Cort didn't; his immediate follow-up films were minor and in 1979 he was in a car accident that almost killed him and pretty much killed his career. He worked steadily in character parts and the rare low-budget lead after that, and in later years, when au courant directors put him in their movies – Kevin Smith with "Dogma," Wes Anderson with "The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou" – it was as a nod to our collective fondness for Harold and for the communal gathering "Harold and Maude" once represented, the midnight audience having long since dissipated into the dawn.

For me, coming across Cort in a latter-day role was always a bit of a shock. Even stranger, it served as a way of catching up with an older younger self – the mirror scene in "Duck Soup" replayed as a dance with a psychic doppelgänger I outgrew a long time ago. If Groucho was the father I once wanted to be, Brewster and Harold and Bud Cort were the boy I had been, dancing up the hill toward freeze frame. But the thing about life – the great and terrible and wonderful thing – is that it just keeps going.

Leave a comment or add to someone else's.

Feel free to forward this to friends if you'd like. If you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and join the discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be grateful — here’s how: