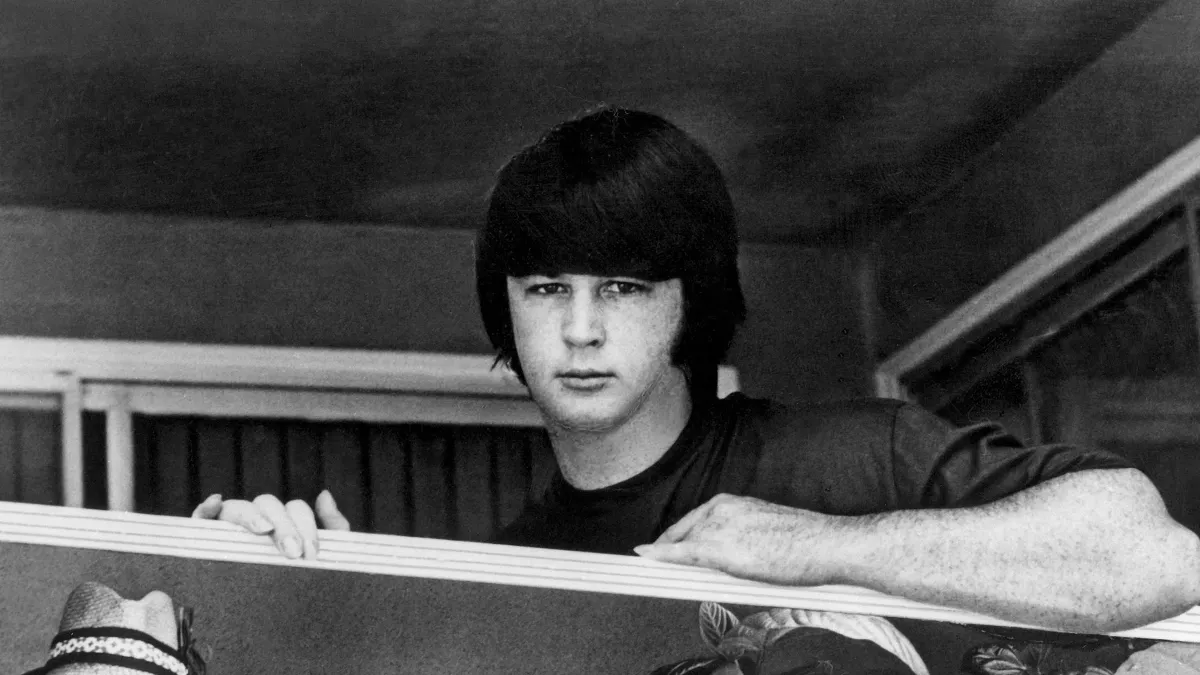

Brian Wilson 1942-2025

We just weren't made for his times.

I like to think that he is finally at peace. That the voices in his head, the ones he said he heard telling him he was worthless every day of his adult life, are stilled. That the sound of his father pounding on the bedroom door is gone, that Dr. Landy is gone, that the terror that made him think his own songs were setting fire to Los Angeles is gone.

Brian Wilson gave us untold sonic pleasure and profound sonic melancholy, and he suffered for it more than you or I will ever know, despite the tell-all books and two-part biopics. What must it be like to be the architect of America's sunniest, most confident dream of itself while knowing the truth of the darkness inside split-level suburbia? "In My Room" – a B-side to "Be True to Your School" that lasts 2 minutes and 17 seconds and is one of the most perfect pop creations of the 20th century – "In My Room" is Brian's confession, in 1963, that it was all a lie: Rhonda, the Midwest's farmer's daughters, the warmth of the sun, the forever of the surf. The only place to feel things, to really, truly feel them, is in the seclusion and security of a room of your own.

"In My Room"

Well, maybe the other place to feel things is in a recording studio, which Brian mastered as an instrument in itself, playing the Wrecking Crew and the sonics of Gold Star and Western like keys on a piano. The Beatles, the Stones, Dylan – they all had producers (George Martin, Andrew Loog Oldham, Tom Wilson), and that's why they sound like they do. The Beach Boys had Brian, and their sound was the sound inside his own head. Which owed a ton to Chuck Berry, doo-wop, The Four Freshmen and Phil Spector in the early days and was gradually filled in with instrumentation and arrangements, melodies and desolation, as the Sixties gathered force. (You can even hear Brian reverse engineer the Beatles in order to figure out what makes them tick in 1965's "Girl Don't Tell Me," which swipes the guitar strums from "You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" and turns "Ticket to Ride" inside out for the chorus. For all his eccentricities and talent, the man was the most competitive tunesmith on the scene.)

"Girl Don't Tell Me"

The turning point is generally acknowledged to be "The Beach Boys Today!" from 1965, with a Side 2 that establishes the beachhead that "Pet Sounds" would use as its launching point. The songs were moody and interior – "Please Let Me Wonder" (i.e., let me stay in my room), "She Knows Me Too Well" (about an abusive relationship), "In the Back of My Mind" with its cacophonous final chord, as if the orderly precision of a classic Beach Boys song had finally rotted through and given way. And that's not even counting the quasi-incestuous "Don't Hurt My Little Sister" on Side 1!

"She Knows Me Too Well"

The label hated those songs, whatever passed for rock critics in 1965 were confused by them, and most of the teenagers who bought the record probably just skipped over the tracks. The other Beach Boys still trusted him, but I bet Mike Love was already getting worried. But Brian knew. He knew there were teenagers out there who didn't fit in, who liked the dark and who treasured their sadness like a hand-cupped candle because it was real and it was theirs. In those Side 2 songs on "The Beach Boys Today!" you can hear the first faint stirrings of emo and goth – the sound of the other Young America.

"Pet Sounds," in 1966, was made for them, but it took the world a long, long time to catch up to it – time enough for alt to become mainstream and for disaffection and disillusionment to become the common coin of adolescence. From the opener, "Wouldn't It Be Nice?" (and wouldn't it? but it isn't), to a final track, "Caroline, No" (the title a novel in itself), that plays like a last farewell to innocence before the beach gets paved over, the album is siffused with a fondness and grief for the joy you can't quite reach anymore and that maybe was never there. The looping massed harmonies at the end of "You Still Believe in Me" are a receding hope, glorious but lost in the fade-out with the bicycle horn. "Don't Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder," "Let's Go Away for Awhile," "I Know there's an Answer," "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times" – what on earth did these black clouds of beauty have to do with America in 1966?

And "God Only Knows" – along with "Good Vibrations" Brian Wilson's finest hour – is merely maybe the purest prayer of devotion ever put on wax, a tower of gossamer instrumentation and harmonies, weaving and interweaving like Bach's own maypole until the voices pile into the sky and Brian ascends to the heavens, leaving us below to pick up the pieces and play the record again. And again. Like Paul McCartney, stunned into the realization that he's been skunked and that the guy writing ditties about fun, fun, fun is as great a songwriter and studio craftsman as he and John are, maybe a better one, and they'd better get on the stick and write "Sgt. Pepper."

"God Only Knows"

After that, madness descended. There were moments of glory, and the pieces of "Smile," the 1967 album that broke Brian's mind and sent him to his room for over a decade, are glittering indeed. Those sessions finally came out in toto in 2011, and there you can find Brian's piano demo for "Surf's Up," which would be rescued by brother Carl for the 1971 album of that name but which is in its truncated solo version perhaps the clearest glimpse into a solitude that nothing, not even music, could assuage. The lyrics by Van Dyke Parks are some kind of piffle, but Brian treats them as pieces of sound; he's more intent on the rise and flow of the melody as the song moves through the multiple chambers of its construction. And then, in the final minutes, he turns the corner into the title – "Surf's up, mm-hmm" – and he's forgotten what comes after that, but it doesn't matter, because with those two words he lowers the entire genre of surf rock gently into its grave. And when he sings the words "a children's song," his voice lifts up into the purest expression of loneliness I have ever heard in my life. He repeats it: A howl, a keening, a stake in the ground, a plea to be heard – and then he muffs a note on the piano and someone in the control room says something, and that's it, it's over. But he touched it there, for a moment, pulled it down and gave it to us, cupped in his hand.

"Surf's Up: Piano demo"

A lot of people today are echoing the title of the "Pet Sounds" track "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times," using it as a eulogy – Brian Wilson just wasn't made for these time, and isn't it sad? Well, yes, but I wonder if it misses the point. Which is that he went mad in part because he couldn't get all the sounds in his head out onto a record, but also because the sounds he did get out we didn't hear, receive, or treasure in the way he needed and they deserved. That Brian Wilson was made for our times. We just weren't made for his.

A playlist I made some while back was helpful in writing this piece. It's below if you'd like to listen to it. (Here's a link to take you to it, too.)

Please feel free to offer your thoughts or stand up for your favorite Wilson song. Comments are open to all today.

Please forward this to friends if you'd like. And if you’re not a paying subscriber and would like to sign up for additional postings and to join the other discussions — or just help underwrite this enterprise, for which the author would be very grateful — here’s how. And thank you.