Baby, Driver

The glorious, tedious splendor of "Annette" comes to VOD

A few words about “Annette,” which comes to Amazon Prime today (Friday, August 20) after a theatrical launch two weeks ago. The opening sequence is one of the most exhilarating movie moments I’ve experienced in months. The final scene is one of the most emotionally overwhelming. It’s the stuff in the middle that feels like work.

We first see director Leos Carax in a control booth, tapping the mic and asking: “So… may we start?” In the recording studio, Ron and Russell Mael of the venerable odd-rock group Sparks cough and clatter their instruments and cue the band into the opening number, which is titled… “So May We Start?” The song picks up speed, a jaunty tune with built-in forward momentum, and suddenly the band and Carax and his crew are out of the studio onto the nighttime streets of Santa Monica, the stars of “Annette” joining them: Adam Driver, Marion Cotillard, Simon Helberg, a bevy of back-up singers, a boys’ choir. It’s an irresistible sidewalk singalong, and we’re all invited into the frame. We are being promised joyful things.

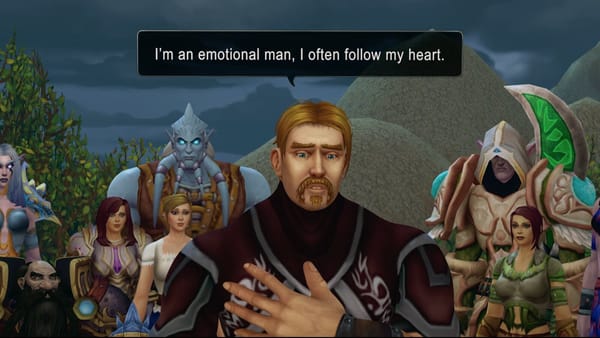

And then the movie proper begins, and it is not joyful. It is, in fact, opera – a passion play of volcanic emotions and brutal behavior writ on an intentionally broad and dark canvas. “Annette” is the story of a famous stand-up comedian – an assault artist – who falls in love with a famous opera singer, who gives birth to their title child, who becomes famous on her own dreamlike terms. Mostly it’s the story of how the comedian, Henry McHenry, goes from bad to worse to monstrous over the course of two hours and twenty minutes of movie. Here’s the thing: We’re over-addicted as a culture to lead characters who might be attractively “bad” but are rarely actively villainous, and Carax has fashioned a narrative that harks back to more primal parables, the kind that existed before Hollywood came along to paper over the cracks. All good, and Driver, love him or hate him, gives a performance that is remarkable in its tortured physicality and willingness to go into the dark.

It’s the story’s development and the way it’s yoked to the Maels’ chant-like, unmodulated score that turns many of the middle scenes in “Annette” into a slog. After their early years of parodic prog-rock in the 1970s, Sparks mined a vein of post-disco dance music that leaned beguilingly on repetition. The effect could be mesmerizing in songs like “My Baby’s Taking Me Home,” which repeats the title phrase over 100 times until it seems to pass through every emotion available to the human species. Their score for “Annette” is heavy on Sprechgesang, characters barking lyrics made of choppy phrases and truncated melodies; the longer numbers, like the duet “We Love Each Other So Much,” are intentionally simplistic tunes that acquire their power through their very genericism. When it works, the movie is rich and strange, unlike anything you’ve ever seen. When it doesn’t, it’s fairly dull.

Ty Burr’s Watch List is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. Those who want to support my work are encouraged to take out a paid subscription.

I will say this: I’ve seen “Annette” twice, once on a movie screen a month ago and once this week on a big-screen TV, and the two experiences don’t begin to compare. As I noted a few weeks ago, a Carax movie needs to wrap itself wholly around your head if it’s to pull off its magic tricks, and “Annette” is even more purposefully removed from realism than “Holy Motors,” which remains the director’s masterpiece. If Tim Burton and Bertolt Brecht had a baby, you might end up with something like this, and if that sounds like a very particular kind of Frankenstein monster, I suspect Carax is okay with that.

Throughout the movie, Annette is presented to us as a realistic animatronic marionette in a way that seems merely weird but that turns out to carry a powerful metaphorical meaning. It’s definitely a haul getting there but the payoff is worth it, a hushed climactic reveal that took my breath away (both times) followed by a duet that is almost unimaginably potent, both for the rawness of its emotions and for the stunning performance of one of the participants. (Hint: It’s not Driver.)

It may even be that lurking behind the baroque scrim of “Annette” is a guilt for all the things parents do to their children – the Larkin-esque damage we visit upon them, the way we turn them into puppets for our unrealized hopes and dreams. It’s hardly a coincidence that we glimpse the adolescent Nastya Carax over her father’s shoulder in the control room at the start of the movie, or that the film is dedicated to her (as “Holy Motors” was dedicated to her late mother), or that the director is on record as not having wanted to proceed with “Annette” until Nastya signed off on it. This is clearly a film about a man with a daughter made by a man with a daughter. Or maybe I just say that – and see that – as a man with daughters of his own.

If you enjoyed this edition of Ty Burr’s Watch List, please feel free to share it with friends.

Or subscribe. Thank you!